There is little that compares to the purity of FreeRide beyond the resort boundaries. Riding the backcountry reminds us of our own personal insignificance. Nothing else matters in these moments. The world beyond the mountain, beyond the next turn, ceases to exist.

For many, part of the thrill comes from the increased exposure to risk. Have I made the right decisions? Do I have the skills? What do I know about Avalanche Avoidance? No matter how experienced we are, the mountain can always surprise us.

Sadly, too many riders who venture beyond the piste are blind to the risks. Not only do they unknowingly put themselves in danger but their thrills are cheap. To ride without an appreciation of what is at stake, only diminishes the experience. Some might argue it is not FreeRide at all.

Avalanches (see anatomy of an avalanche) are one of the greatest dangers that riders face, and the least predictable. Accidents are almost always triggered by a complicated interaction between weather, snowpack, terrain and human activity.

Predicting when an avalanche may occur is complicated, but recognising avalanche terrain where they can occur is relatively simple.

Even when snowpack instability is high, avalanches will only occur on terrain with certain features and characteristics. Knowing how to recognise avalanche terrain is crucial to all who seek to ride the uncontrolled mountain.

Slope angle, shape, orientation and altitude.

The shape of a slope, it’s angle, orientation and altitude are all factors the FreeRider needs to consider when scoping a line.

Slope angle.

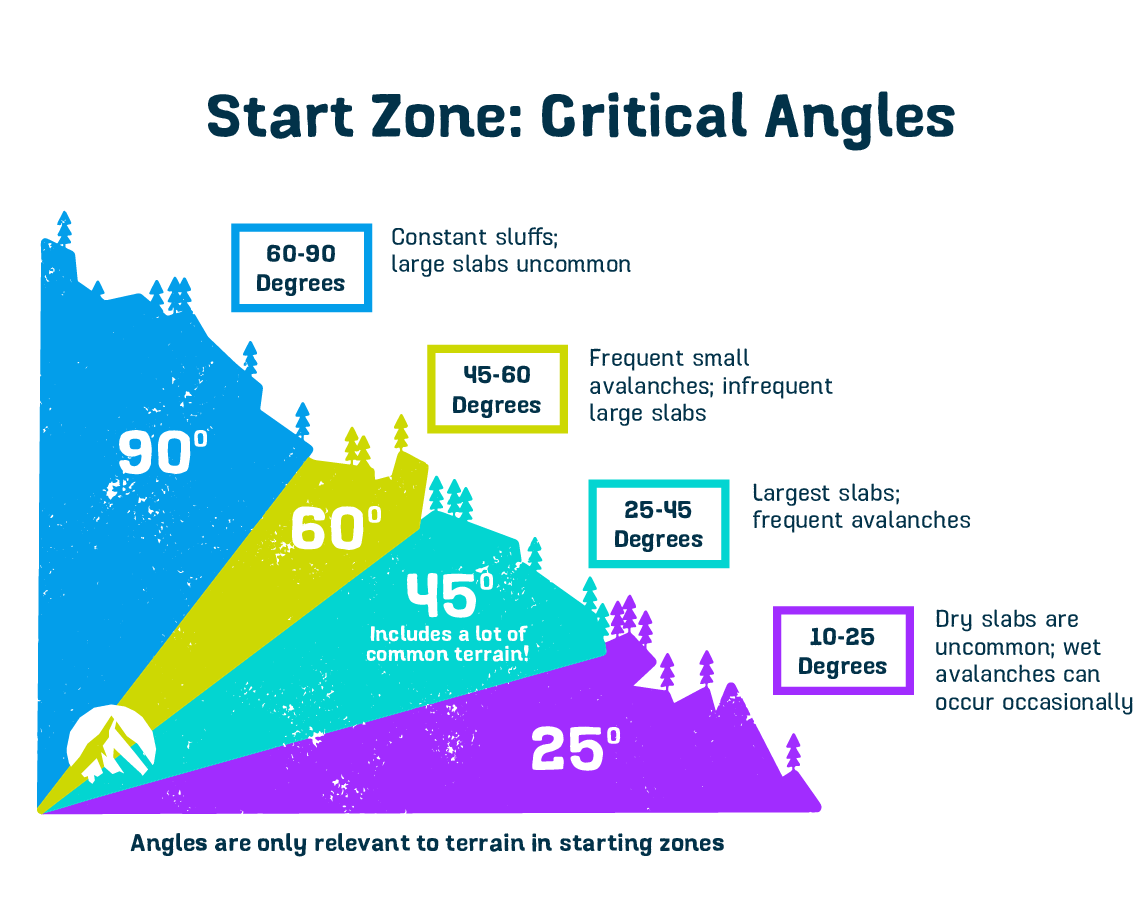

Avalanches occur when the pull of gravity overcomes the frictional forces holding the snow in place. The steeper the slope, the greater the likelihood of an avalanche. Knowing the angle of the slope you’re about to ride is essential in assessing the probability of a slide. Here are some of the key stats you’ll want to know as a FreeRider:

Our sense of steepness is subjective; based on our relative skills and experience. However, in spite of our ability to vibe out the steepness within our riding zone, we are much less capable of accurately judging slope angles. To the human eye the difference between 33° and 38° is imperceptible but it could be the difference between a life-affirming FreeRide or a life threatening slab avalanche. Unless you’re comfortable riding with this kind of uncertainty, you’re going to want to know the slope angle before you drop in.

Slope shape

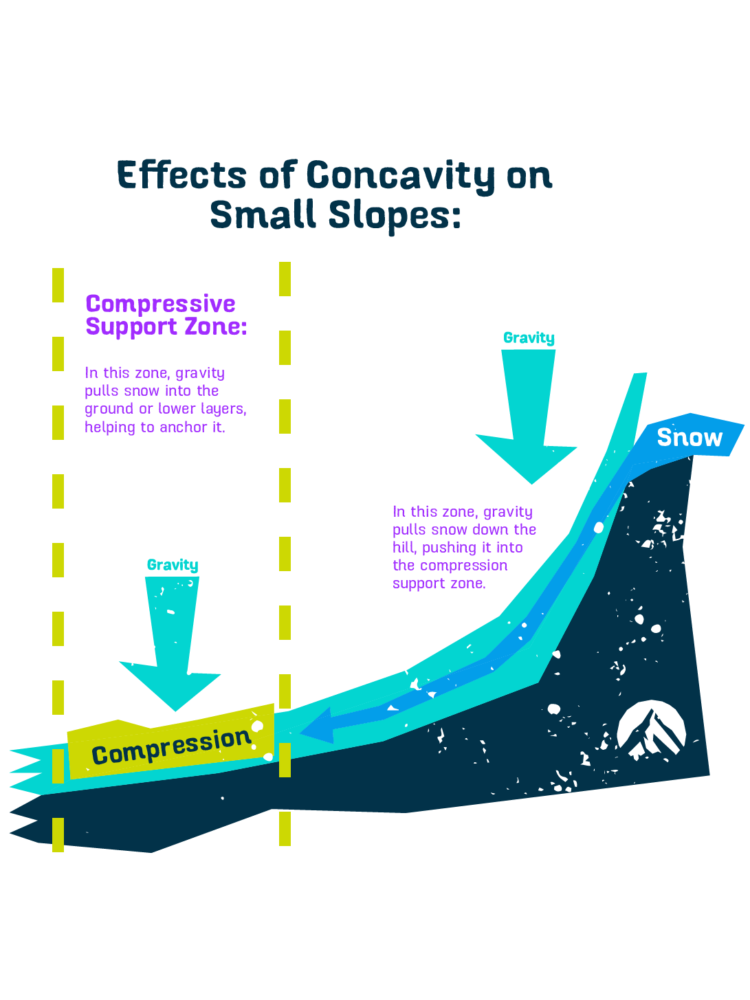

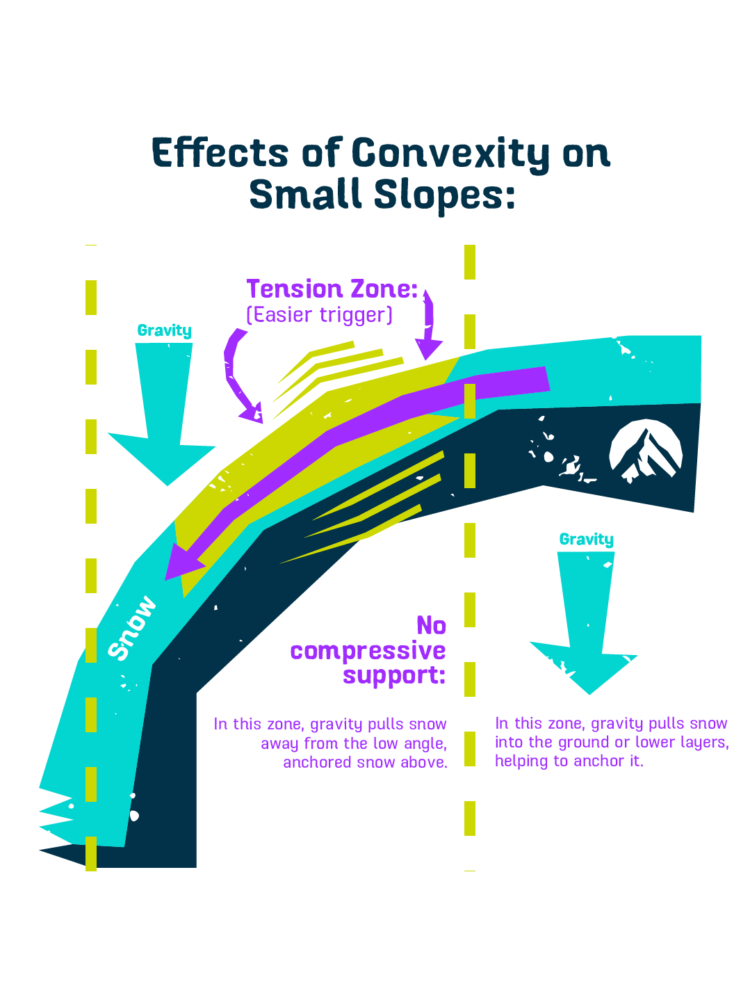

The shape of a slope also influences the probability of a slide so it’s important to know and recognise the difference between concave and convex slopes (see anatomy of an avalanche). Convex slopes tend to be more risky as they create tension in the snowpack which causes weakness and fracture points.

Slope aspect or orientation

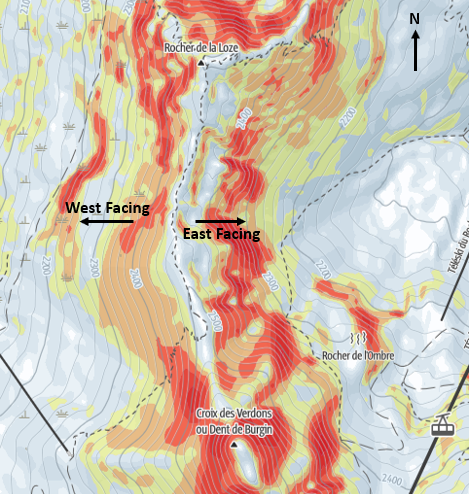

Slope aspect is the compass direction a slope faces. For example, the ridge line running due north from the Croix de Verdon to the Rocher de la Loze has both an east facing and west facing aspect.

Slope aspect has a major influence on avalanche risk, but unlike angle and shape which are constant, the impact of the slope aspect is variable. For example, north facing slopes tend to be more avalanche prone in winter, but by spring, south facing slopes may present a greater hazard.

Why do the seasons and slope aspect matter when trying to recognise avalanche terrain?

In general terms this is because north facing slopes receive less sun in winter to melt and condense the snowpack. However, by spring south facing slopes may become over-exposed to sunshine leading to dangerous wet snow slides.

The orientation of a slope with respect to the wind is another biggie when it comes to avalanche formation. Wind distributes snow unevenly and, during storms, will pick up loose snow and transport it from one slope to another. Unstable wind slabs often form on downwind (lee) slopes following a storm and can release as slab avalanches. Wind blown snow is not your friend!

Slope altitude

Altitude or elevation – how many metres you are above sea level – also has a significant impact on avalanche risk. At a higher elevation, temperatures are lower and precipitation and wind speeds tend to be higher, all of which impacts slope stability. It is also generally the case that slopes become steeper and above the treeline there is no forest cover stabilising the snow and preventing avalanches from triggering. Freeriders need to exercise greater caution at higher altitudes.

As long as we paid attention in Geography class it’s relatively easy to identify concave and convex slope shapes but it’s a good idea to add an inclinometer, compass and altimeter to your FreeRide checklist. You should also pay close attention to the wind direction in the days before you venture into the backcountry.

Terrain traps

It’s not enough to only consider whether your presence on the slope will trigger an avalanche; you should also assess where the avalanche will take you and what the consequences would be. Terrain traps magnify the impact of being caught in a slide. Being swept over a cliff, into a bowl or through trees is likely to have an adverse effect on your well being. If you don’t like the look of where you might end up in the event of a slide then it’s wise to choose another slope. When considering your line, you should also look for escape routes to safer terrain in the event of a slide.

Connected terrain

On top of your awareness of terrain traps below, it’s also necessary to consider connected terrain. For example, if you’re planning to traverse into a line it’s important to know the terrain above you. A cornice may be a risk factor and could also indicate the presence of unstable wind slabs on the slope you are assessing. The size of the face you are on is also a significant factor. The larger the face the greater the potential fracture line and overall size of avalanche.

History

Avalanches tend to recur and often leave clues of their past in the landscape. It’s unwise to ignore avalanche debris and fracture lines in the snowpack. The absence of trees or the presence of small immature or stunted trees on an otherwise wooded slope may indicate the path of successive slides. There’s no guarantee that a slope that has never avalanched before will not slide given the right conditions, but when it comes to avalanches, history often repeats itself.

Fear is good

No matter how much you know about avalanches and how careful you are at reducing exposure to its hazards, you’re always at risk when you venture into the backcountry. It’s up to you to decide the risk profile that’s right for you, but don’t be ignorant when it comes to recognising avalanche terrain. If you don’t like where an avalanche might take you or the consequences of what might happen, then don’t venture onto that slope. Fear can help you make the right decision. Fear is a call to think carefully, and you should listen to it.

Do you have anything you want to share with the Republic?

Photo’s or examples of avalanche terrain?

Practical advice for anyone heading into the backcountry?

Personal accounts or experiences you’d like to share?

Add your comments below.

Looking for source material from avalanche experts? Try these:

Explore the themes below to find the best home for the content you want to learn about: